Shared mobility in urban development planning

In recent years, shared mobility in urban development planning has become an important and promising trend. Research into the frameworks and standards that municipalities can deploy to capture the potential of shared mobility is ongoing.

Note: this article is a liberal extract and translation of the Dutch publication Deelmobiliteit in gebiedsontwikkeling.

From parking policy to a broader mobility policy

Limiting car ownership is becoming a key metric in urban development planning, as scarce urban space can be designated only once. In many urban developments, municipalities prefer to allocate the public space for social and community functions rather than use it for parking and infrastructure to facilitate passenger cars.

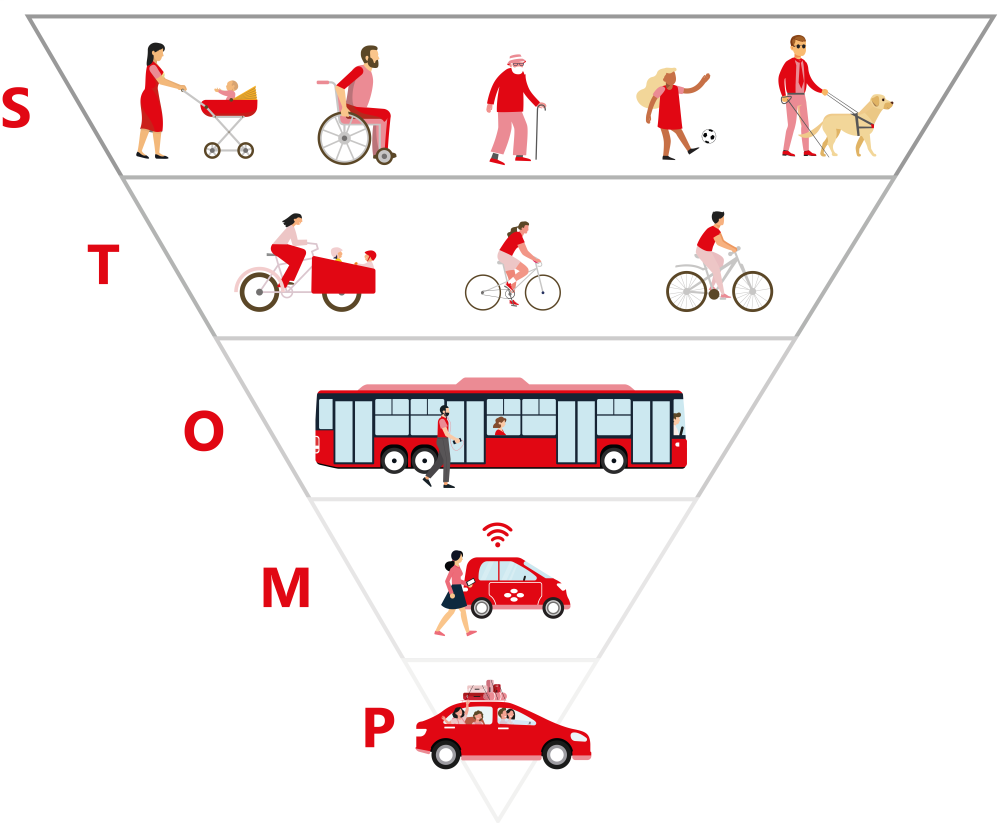

Regardless of the scale and nature of the urban development or transformation, good accessibility remains an important part of the infrastructure. And accessibility is increasingly being provided for by a broader mobility policy (according to the STOMP1principles), which means that parking policy is now part of the wider considerations for space and mobility issues.

STOMP Principle

Fewer parking spaces means more shared mobility

Less space for (parked) cars or bicycles is often compensated by providing an easily accessible network of transport alternatives, mainly public transport within walking or cycling distance.

However, in larger, more complex urban areas, shared mobility schemes are increasingly becoming part of the mobility policy.

In many of the projects examined, space taken from private parking was allocated to shared mobility solutions. In other words, enabling shared mobility goes hand in hand with reducing the parking space standard. This means a developer may create fewer parking spaces if they make provisions for shared mobility.

Resistance to reducing the parking space standard

Shared mobility is a promising instrument in the transition to alternative and sustainable mobility concepts. However, considerable effort is needed to effect a change in residents' mobility habits and to tempt them to abandon car ownership.

Translating a municipal mobility policy to an area-specific plan is often a difficult task. Currently, there are no guidelines for translating the allocation of space and density of an area, applying the STOMP principles, and fulfilling the demands and constraints of various target groups.

It is also noted that policy is often insufficiently translated into requirements for maintaining the shared mobility offering in the operational and usage phase. Furthermore, the role of developing parties in this longer-term goal is unclear.

Shared mobility at plot or area level?

Shared mobility at plot level requires relatively more space and more vehicles to meet the same demand. Shared mobility as a collective initiative seems to focus more on the quality (availability and sharing formulas) and less on simply the number of vehicles available. Collective initiatives also offer greater flexibility (dividing availability across multiple locations) and can tailor communications and product offering to the needs of the area served.

Larger and more complex developments that are designed to minimise car use, increasingly have shared mobility organised at area level. Mobility Hubs are created to meet the collective needs of all groups in the area, and usually include visitor parking. This is often accompanied by an area-specific mobility policy and a more robust organisational structure to facilitate operating shared mobility in the area for the longer term.

Uncertainty regarding use of shared mobility

In practice, we see very few successful examples of shared mobility in urban developments. Many existing projects are based on reducing the parking space standard with a prerequisite of x spaces for cars. This calculation is too simple and does not work without proper integration of the broader STOMP mobility policy objectives.

And, more often than not, agreements with developers do not include enforceable obligations. For example, to offer shared mobility for many years, including efforts that ensure the shared mobility offering as agreed upon remains available. Such schemes have no chance of succeeding if the agreements not enforced.

Shared mobility at area level or throughout the city

It is not enough to simply offer shared cars The success of shared mobility initiatives also depends on the municipality's accompanying mobility policy. For example, if a municipality does not regulate car parking in an area development, implementing shared mobility will be virtually impossible.

Shared mobility and governance

For a significant proportion of Dutch municipalities, it is not (yet) clear how actively they are encouraging shared mobility. We see municipalities shifting from a minimal role (setting the framework) to a more involved role (influence through (co-)ownership in the area), thus taking matters into their own hands and having greater influence on the offering and operation of the shared mobility concept in the urban development.

However, this requires a willingness as a municipality to take investment and operational risks in an ongoing transition.

Challenges

Dealing with uncertainties and guarantees over time.

Taking into account the interests of other parties – there are three key actors involved in shared mobility (municipalities, developers, service providers):

Municipalities want to facilitate a feasible sustainable mobility plan within the shared mobility concept.

Developers want to provide suitable homes for rent or sale to meet the target group's needs while achieving a return on their investment and thereby managing their risks.

The service providers endeavour to make an appealing business case for new residents.

Other considerations

Communication – Timely and proper communication to current and future residents regarding mobility policy is crucial for the success of shared mobility in urban developments. There's a real danger of fragmentation because municipal policy is designed to bring about a mobility transition, while developers and estate agents are only concerned about the marketability of the objects in the development.

Monitoring – To successfully implement a mobility concept in urban developments, it is essential to monitor shared mobility usage. Agreements between the municipality, developer and shared-mobility providers usually do not include sharing data or information with the municipality. This often means there is no information regarding the use of the shared mobility service offering.

Findings

Despite experience gained in recent years with shared mobility in urban developments, there are still many questions and choices, and the chances of success remain uncertain.

A transition from parking policy to mobility policy is needed if shared mobility is to become the new norm, and this also requires alternative, broader considerations and frameworks.

Ingredients in the recipe for failure include:

trading a reduced number of parking spaces for private cars with a number of shared cars per residence;

the municipality neglecting to make binding agreements with the developer.

Municipalities have no or insufficient insight into actual usage and have not given enough thought to monitoring and tools to maintain and manage the shared mobility offering.

Communication to current and future residents regarding the mobility policy consequences such as parking permits, visitor parking, and the shared mobility offering is often incomplete or non-existent.

Grip on success increases with a neighbourhood wide approach and implementation which focuses on cooperation and agreements between parties regarding quantity, quality, communication as well as usage.

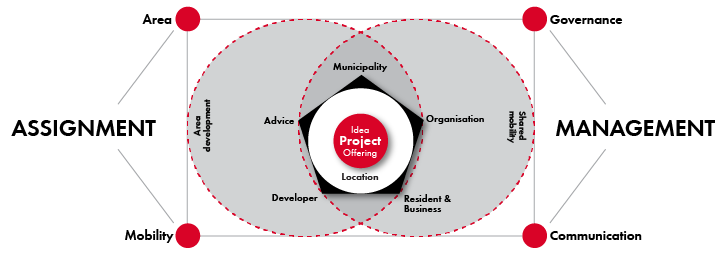

Municipal management and smart choices

Mobility is a key issue in any complex urban development plan, but is also an organisational issue when it comes to how mobility, including shared vehicles, is managed in the area. As shared mobility schemes are relatively new, it will only be possible to measure their success over time.

We cannot predict how mobility behaviour will have developed in 10 years' time. The key is to make smart choices now, to be realistic about the potential use of shared mobility and leave scope for necessary future policy changes. This means that municipalities must play a significant role in the organisation and operation of shared mobility.

Making plans for the future always includes an element of uncertainty, especially as the lead time for housing construction and mobility policy is at least 15 to 20 years.

Tips for shared mobility in urban planning

Focus municipal mobility policy by creating specific shared mobility standards and requirements and specify these per urban development project to gain experience.

Define policy but leave scope for individual agreements per project or per project phase. The market is changing rapidly, so delay making firm agreements, which will allow municipalities to respond better to (unforeseen) market developments.

Together with developers and operators, ensure control over the shared mobility offering and implementation. Do not plan shared mobility at plot level, as this reduces control over mobility in the wider urban area.

Be realistic about the potential for shared mobility and do not allocate too little space to parking too quickly without making provisions for future policy changes.

Work together with developers to fulfil shared mobility agreements for the entire urban area, at the same time, consult with and leverage experiences from multiple shared mobility providers.

Commit to proper, regular communication to realise the full potential.

As municipality, make agreements with the developer regarding monitoring mobility and shared mobility usage in all phases of the project. This way, the municipality will not be surprised by complaints or a reduced service offering.

Municipalities must support shared-mobility operators

Resources for the process and organisation

Municipalities should encourage (organisation, roles and communication) and provide greater guidance (including financial stimuli) to bring about socially relevant behavioural changes in mobility.

Solving shared mobility issues on a small scale (neighbourhood level) seems attractive and easier to implement, but in the longer term, shared mobility is part of a more extensive multimodal mobility system.

After all, urban development provides for multiple societal groups. Besides services for residents, shared mobility in an urban development must connect seamlessly with urban networks of shared mobility services for visitors. This means that implementation at street level, or in covered/underground parking facilities, can also fulfil a hub function for shared bicycles or scooters (single trips, free floating).

Shared mobility is an integral part of the multimodal mobility system

Perseverance required

Because the effects of shared mobility usage or supply constraints are not yet known, it is not possible to predict the consequences of not succeeding. For that matter, facilitating shared mobility services as a substitute for parking spaces and thus meeting municipal requirements requires financial commitment, coupled with an expected payback period, and includes a legal obligation to provide services for ‘at least’ 10 years. Any changes the municipality may make to the zoning plan will disrupt the agreements and expectations.

And neither can a developer simply dismiss a shared mobility project after only a few years. Passing this responsibility on to a shared mobility provider does not seem to create adequate guarantees.

Planning large urban developments

It is encouraging to see that municipalities are working on policy for parking and other mobility modes to support their shared mobility policy. This should also include public transport policy so the municipality can manage and encourage the total range of public and private mobility facilities in the entire urban area.

Increasing focus on hubs

Much work still needs to be done before the new mobility and the mobility transition is embedded in our society and urban development planning. Shared mobility provision and usage is still erratic, providers and business models require a flexible and robust strategy, which also places demands on urban development. Mobility hubs, preferably modular ones, play a major role as they combine hardware (parking), software (shared mobility offering) and orgware (commercial operation and financing).

It is essential that public and private parties work together, as knowledge and expertise is required for parking management and other mobility services.

Despite the risks and uncertainties, it is becoming increasingly clear how mobility hubs can play a key role in urban developments. Planning, construction and commercial operation are inextricably linked and should be approached accordingly. Public-private partnerships offer good opportunities, especially when all parties make optimal use of their own knowledge and experience. Despite the many issues involved in tendering, there is much to be said for working together on standardisation, efficiency and interchangeable hubs.

Suggestions to develop shared mobility policy

Develop guidelines for drawing up, monitoring and evaluating performance agreements.

Develop standards and apply these to business cases for hubs and various implementation models regarding ownership and commercial operation.

Shared mobility success model

Source: Report on shared mobility in urban development planning (Rapportage deelmobiliteit in gebiedsontwikkeling) drawn up by knowledge partners APPM, Deesy, Stadkwadraat and Witteveen + Woodland. 13 September 2024 Commissioned by: Natuurlijk!Deelmobiliteit, part of the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management

- STOMP stands for prioritising sustainable mobility over private car use. In this Dutch acronym the S for 'Stappen' translates to walking, the T for 'Trappen' to cycling, the O for Openbaar Vervoer to public transport, the M is for Mobility as a Service (MaaS, i.e. shared mobility) and the P is for Private car.